US Gold Coins

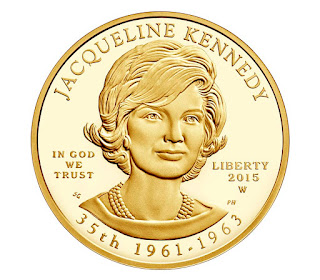

Jacqueline Kennedy 2015 10 Dollars First Spouse Gold Coin

First Lady of the United States, 1961 — 1963

Obverse: “JACQUELINE KENNEDY,” “IN GOD WE TRUST,” “LIBERTY,” “2015,” “35th” and “1961 – 1963.”

Jacqueline Kennedy was born Jacqueline Lee Bouvier on July 28, 1929. She grew up on an estate called “Merrywood,” near Washington, D.C., the home of her mother's second husband, and was educated in private schools and studied ballet. She began attending Vassar College, spent her junior year of college in France and graduated from George Washington University. When she took a job as a photographer for a local Washington newspaper, she met then-Senator John F. Kennedy, and they married in 1953. Mrs. Kennedy brought a strong interest in the arts to the White House. Fluent in several languages, she charmed world leaders at the White House and on trips abroad. Co-founder of the White House Historical Association, she gave a televised tour following its renovation. She displayed courage and poise in the White House — staying during the Cuban Missile Crisis despite being advised to relocate to an underground shelter. That courage and poise was also on display during her husband's assassination, the swearing in of his successor Lyndon Johnson and during President Kennedy's televised funeral. After leaving the White House, from 1978 to her death in 1994, she was an editor at Doubleday, a publishing firm in New York City.

The reverse features the species of saucer magnolia Mrs. Kennedy chose to be planted in the White House garden and near the eternal flame at her husband's grave at Arlington National Cemetery. The petals stretch across the globe, its tips connecting the points of some of her most notable diplomatic visits.

Inscription: “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,“ “E PLURIBUS UNUM,” “$10,” “1/2 OZ.” and “.9999 FINE GOLD.”

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

US Gold Coins

First Spouse Gold Coins Program

2007 First Spouse Gold Coins

2008 First Spouse Gold Coins

2009 First Spouse Gold Coins

2010 First Spouse Gold Coins

2011 First Spouse Gold Coins

2012 First Spouse Gold Coins

2013 First Spouse Gold Coins

2014 First Spouse Gold Coins

2015 First Spouse Gold Coins

Jacqueline Kennedy Mamie Eisenhower Bess Truman Lady Bird Johnson

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis (née Bouvier; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was the wife of the 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, and First Lady of the United States from 1961 until his assassination in 1963.

Bouvier was the elder daughter of Wall Street stockbroker John Vernou Bouvier III and socialite Janet Lee Bouvier. In 1951, she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in French literature from George Washington University and went on to work for the Washington Times-Herald as an inquiring photographer.

In 1952, Bouvier met Congressman John F. Kennedy at a dinner party. In November of that year, he was elected as a United States Senator from Massachusetts, and the couple married in 1953. They had four children, two of whom died in infancy. As First Lady, she was known for her highly publicized restoration of the White House and her emphasis on arts and culture. On November 22, 1963, she was riding with the President in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas, when he was assassinated. She and her children withdrew from public view after his funeral, and in 1968 she married Aristotle Onassis.

Following her second husband's death in 1975, she had a career as a book editor for the final two decades of her life. She is remembered for her lifelong contributions to the arts and preservation of historic architecture, as well as for her style, elegance, and grace. She was a fashion icon, and her famous ensemble of pink Chanel suit and matching pillbox hat has become a symbol of her husband's assassination. She ranks as one of the most popular First Ladies and in 1999 was named on Gallup's list of Most Admired Men and Women in 20th-century America.

Wedding and early years of marriage to John F. Kennedy

Bouvier and U.S. Representative John F. Kennedy belonged to the same social circle and were formally introduced by a mutual friend, journalist Charles L. Bartlett, at a dinner party in May 1952. Bouvier was attracted to Kennedy's physical appearance, charm, wit and wealth. The couple also shared the similarities of Catholicism, writing, enjoying reading and having previously lived abroad. Kennedy was busy running for the U.S. Senate, and the relationship grew more serious after the November election, when he proposed to her. Because Bouvier had been assigned to cover the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in London for The Washington Times-Herald, she took some time to accept. After a month in Europe, she returned to the United States and accepted Kennedy's marriage proposal. She then resigned from her position at the newspaper. Their engagement was officially announced on June 25, 1953.Bouvier and Kennedy were married on September 12, 1953, at St. Mary's Church in Newport, Rhode Island, in a mass celebrated by Boston's Archbishop Richard Cushing. The wedding was considered the social event of the season with an estimated 700 guests at the ceremony and 1,200 at the reception that followed at Hammersmith Farm. The wedding dress, now housed in the Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts, and the dresses of her attendants were created by designer Ann Lowe of New York City.

The newlyweds honeymooned in Acapulco, Mexico before settling in their new home, Hickory Hill in McLean, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C. Kennedy developed a warm relationship with her in-laws, Joseph and Rose Kennedy. In the early years of their marriage, the couple faced several personal setbacks. John Kennedy suffered from Addison's Disease and from chronic and at times debilitating back pain due to a war injury; in late 1954, he underwent two near-fatal spinal operations. Additionally, Jacqueline suffered a miscarriage in 1955 and in August 1956 gave birth to a stillborn daughter, Arabella. They subsequently sold their Hickory Hill estate to John's brother Robert, who occupied it with his wife Ethel and their growing family, and bought a townhouse on N Street in Georgetown.

Jacqueline gave birth to a daughter Caroline on November 27, 1957, via Caesarean section. At the time, she and John Kennedy were campaigning for his re-election to the Senate, and they posed with their infant daughter for the cover of the April 21, 1958 issue of Life. They traveled together during the campaign, trying to narrow the geographical gap between them that had persisted for the first five years of the marriage. Soon enough, John Kennedy started to notice the value that his wife added to his campaign. Kenneth O'Donnell remembered that "the size of the crowd was twice as big" when she accompanied her husband; he also recalled her as "always cheerful and obliging". John's mother Rose observed Jacqueline as not being "a natural-born campaigner" due to her shyness and being uncomfortable with too much attention. In November 1958, John Kennedy was reelected to a second term. He credited Jacqueline's visibility in both ads and stumping as vital assets in securing his victory, and he called her "simply invaluable".

In July 1959, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger visited the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port and had his first conversation with Jacqueline; he found her to have "tremendous awareness, an all-seeing eye and a ruthless judgment". That year, Jack Kennedy traveled to 14 states, with Jacqueline taking long breaks from the trips so she could spend time with their daughter Caroline. She also counseled her husband on improving his wardrobe in preparation for his intended presidential campaign the following year. In particular, she traveled to Louisiana to visit Edmund Reggie and to help her husband garner support in the state for his presidential bid.

First Lady of the United States (1960–1963)

Campaign for presidency

On January 3, 1960, John F. Kennedy announced his candidacy for the presidency and launched his campaign nationwide. In the early months of the election year, Jacqueline Kennedy accompanied her husband to campaign events such as whistle-stops and dinners. Shortly after the campaign began, she became pregnant and decided to stay at home in Georgetown due to her previous high-risk pregnancies. Kennedy subsequently participated in the campaign by writing a weekly syndicated newspaper column, Campaign Wife, answering correspondence, and giving interviews to the media.

Despite not participating on the campaign trail, Jacqueline became subject of intense media attention with her fashion choices. On one hand, she was admired for her personal style; she was frequently featured in women's magazines alongside film stars and named as one of the 12 best-dressed women of the world. On the other hand, her preference for French designers and her spending on her wardrobe brought her negative press. In order to downplay her wealthy background, Jacqueline stressed the amount of work she was doing for the campaign and declined to publicly discuss her clothing choices.

On July 13 at the 1960 Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, the Democratic Party nominated John Kennedy for President of the United States. Jacqueline did not attend the nomination due to her pregnancy, which had been publicly announced ten days earlier. From Hyannis Port, she watched the September 26, 1960 debate—which was the nation's first televised presidential debate—between her husband and Republican candidate Richard Nixon, who was the incumbent Vice President. Marian Cannon, the wife of Arthur Schlesinger, watched the debate with her. Days after the debates, Jacqueline contacted Schlesinger and informed him that Jack wanted his aid along with that of John Kenneth Galbraith in preparing for the third debate on October 13; she wished for them to give her husband new ideas and speeches. On September 29, 1960, the Kennedys appeared together for a joint interview on Person to Person, interviewed by Charles Collingwood.

As First Lady

On November 8, 1960, John F. Kennedy narrowly defeated Republican opponent Richard Nixon in the U.S. presidential election. A little over two weeks later on November 25, Jacqueline gave birth to the couple's first son, John F. Kennedy, Jr., via Caesarean section. She spent two weeks recovering in the hospital, during which the most minute details of both her and her son's conditions were reported by the media in what has been considered the first instance of national interest in the Kennedy family.

When her husband was sworn in as president on January 20, 1961, 31-year-old Jacqueline became the third youngest First Lady in American history—behind Frances Folsom (21) and Julia Gardiner (24). As a presidential couple, the Kennedys differed from the Eisenhowers by their political affiliation, youth, and their relationship with the media. Historian Gil Troy has noted that in particular, they "emphasized vague appearances rather than specific accomplishments or passionate commitments" and therefore fit in well in the early 1960s' "cool, TV-oriented culture". The discussion about Jacqueline's fashion choices continued during her years in the White House, and she became a trendsetter, hiring American designer Oleg Cassini to design her wardrobe. She was the first presidential wife to hire a press secretary, Pamela Turnure, and carefully managed her contact with the media, usually shying away from making public statements, and strictly controlling the extent to which her children were photographed. Kennedy was portrayed by the media as the ideal woman, leading academic Maurine Beasley to observe that she "created an unrealistic media expectation for first ladies that would challenge her successors." Nevertheless, the First Lady attracted worldwide positive public attention and gained allies for the White House and international support for the Kennedy administration and its Cold War policies.

Although Jacqueline stated that her priority as a First Lady was to take care of the President and their children, she also dedicated her time to the promotion of American arts and preservation of its history. The restoration of the White House was her main contribution, but she also furthered the cause by hosting social events that brought together elite figures from politics and the arts. One of her unrealized goals was to found a Department of the Arts, but she did contribute to the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment of the Humanities, established during Johnson's tenure.

White House restoration

Jacqueline had visited the White House twice prior to becoming First Lady, once as a tourist in 1941 and again as the guest of Mamie Eisenhower shortly before her husband's inauguration. She was dismayed to find that the mansion's rooms were furnished with undistinguished pieces that displayed little historical significance and made it her first major project as First Lady to restore its historical character. On her first day in residence, she began her efforts with the help of interior decorator Sister Parish. She decided to make the family quarters attractive and suitable for family life by adding a kitchen on the family floor and new rooms for her children. The $50,000 that had been appropriated for this effort was almost immediately exhausted. Continuing the project, she established a fine arts committee to oversee and fund the restoration process and solicited the advice of early American furniture expert Henry du Pont. To solve the funding problem, a White House guidebook was published, sales of which were used for the restoration. Working with Rachel Lambert Mellon, Kennedy also oversaw the redesign and replanting of the White House Rose Garden and the East Garden, which was renamed the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden after her husband's assassination. In addition, Kennedy helped to stop the destruction of historic homes in Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C., because she felt these buildings were an important part of the nation's capital and played an essential role in its history.

Prior to Kennedy's years as First Lady, furnishings and other items had been taken from the White House by presidents and their families when they departed; this led to the lack of original historical pieces in the mansion. To track down these missing furnishings and other historical pieces of interest, she personally wrote to possible donors. She also initiated a Congressional bill establishing that White House furnishings would be the property of the Smithsonian Institution, rather than available to departing ex-presidents to claim as their own, and founded the White House Historical Association, the Committee for the Preservation of the White House, the position of a permanent Curator of the White House, the White House Endowment Trust, and the White House Acquisition Trust. She was the first presidential spouse to hire a White House curator.

On February 14, 1962, Jacqueline took American television viewers on a tour of the White House with Charles Collingwood of CBS News. In the tour she stated that "I feel so strongly that the White House should have as fine a collection of American pictures as possible. It's so important... the setting in which the presidency is presented to the world, to foreign visitors. The American people should be proud of it. We have such a great civilization. So many foreigners don't realize it. I think this house should be the place we see them best." The film was watched by 56 million television viewers in the United States, and was later distributed to 106 countries. Kennedy won a special Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Trustees Award for it at the Emmy Awards in 1962, which was accepted on her behalf by Lady Bird Johnson. Kennedy was the only First Lady to win an Emmy.

Foreign trips

Throughout her husband's presidency, Kennedy made many official visits to other countries, on her own or with the President – more than any of the preceding First Ladies. Despite the initial worry that she might not have "political appeal", she proved popular among international dignitaries. Before the Kennedys' first official visit to France in 1961, a television special was shot in French with the First Lady on the White House lawn. After arriving in the country, she impressed the public with her ability to speak French, as well as her extensive knowledge of French history. At the conclusion of the visit, Time magazine seemed delighted with the First Lady and noted, "There was also that fellow who came with her." Even President Kennedy joked, "I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris – and I have enjoyed it!"

From France, the Kennedys traveled to Vienna, Austria, where Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, when asked to shake the President's hand for a photo, stated, "I'd like to shake her hand first." Khrushchev later sent her a puppy, significant for being the offspring of Strelka, the dog that had gone to space during a Soviet space mission.

At the urging of U.S. Ambassador to India John Kenneth Galbraith, Kennedy undertook a tour of India and Pakistan with her sister Lee Radziwill in 1962, which was amply documented in photojournalism of the time as well as in Galbraith's journals and memoirs. She was gifted with a horse called Sardar by the President of Pakistan, Ayub Khan, as he had found out on his visit to the White House that he and the First Lady had a common interest in horses. Life magazine correspondent Anne Chamberlin wrote that Kennedy "conducted herself magnificently” although noting that her crowds were smaller than those that President Dwight Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II attracted when they had previously visited these countries. In addition to these well-publicized trips during the three years of the Kennedy administration, she traveled to countries including Afghanistan, Austria, Canada, Colombia, England, Greece, Italy, Mexico, Morocco, Turkey, and Venezuela.

Death of infant son

In early 1963, Jacqueline was again pregnant, leading her to curtail her official duties. She spent most of the summer at a home she and her husband had rented on Squaw Island, near the Kennedy compound on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. On August 7, five weeks ahead of her scheduled Caesarean section, she went into labor and gave birth to a boy, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, via emergency Caesarean section at nearby Otis Air Force Base. His lungs were not fully developed, and he was transferred from Cape Cod to Boston Children's Hospital where he died of hyaline membrane disease two days after birth. Jacqueline had remained at Otis Air Force Base to recuperate after the Caesarean delivery; her husband went to Boston to be with their infant son, and was present at his death. He returned to Otis on August 14 to take her home, giving an impromptu speech to thank nurses and airmen that had gathered in her suite, and she presented hospital staff with framed and signed lithographs of the White House.

The First Lady was deeply affected by the death and entered a state of depression afterward. However, losing their child had a positive impact on the marriage, bringing the couple closer together in their shared grief. Arthur Schlesinger wrote that while President Kennedy always "regarded Jacqueline with genuine affection and pride," their marriage "never seemed more solid than in the later months of 1963." Aware of her depression, Kennedy's friend Aristotle Onassis invited her to his yacht. Despite President Kennedy initially having reservations, he reportedly believed that it would be "good for her." The trip was widely disapproved of within the Kennedy administration and by much of the general public, as well as in Congress. The First Lady returned to the United States on October 17, 1963. She would later say she regretted being away as long as she was, but had "melancholy after the death of my baby."

Assassination and funeral of John F. Kennedy

On November 21, 1963, The First Lady and the president left the White House for a political trip to Texas, the first time she had joined her husband on such a trip in the U.S. After a breakfast on November 22, they flew from Fort Worth's Carswell Air Force Base to Dallas' Love Field on Air Force One, accompanied by Texas Governor John Connally and his wife Nellie. The First Lady was wearing a bright pink Chanel suit and a pillbox hat, which had been personally selected by President Kennedy. A 9.5-mile (15.3 km) motorcade was to take them to the Trade Mart, where the President was scheduled to speak at a lunch. The First Lady was seated next to her husband in the presidential limousine, with the Governor and his wife seated in front of them. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife followed in another car in the motorcade.

After the motorcade turned the corner onto Elm Street in Dealey Plaza, the First Lady heard what she thought to be a motorcycle backfiring and did not realize that it was a gunshot until she heard Governor Connally scream. Within 8.4 seconds, two more shots had rung out, and one of the shots struck her husband in the head. Almost immediately, she began to climb onto the back of the limousine; Secret Service agent Clint Hill later told the Warren Commission that he thought she had been reaching across the trunk for a piece of her husband's skull that had been blown off. Hill ran to the car and leapt onto it, directing her back to her seat. As Hill stood on the back bumper, Associated Press photographer Ike Altgens snapped a photograph that was featured on the front pages of newspapers around the world. She would later testify that she saw pictures "of me climbing out the back. But I don't remember that at all".

The President was rushed to Dallas' Parkland Hospital. At her request, the First Lady was allowed to be present in the operating room. After her husband was pronounced dead, Kennedy refused to remove her blood-stained clothing and reportedly regretted having washed the blood off her face and hands, explaining to Lady Bird Johnson that she wanted "them to see what they have done to Jack". She continued to wear the blood-stained pink suit as she boarded Air Force One and stood next to Johnson when he took the oath of office as President. The unlaundered suit was donated to the National Archives and Records Administration in 1964, and under the terms of an agreement with her daughter Caroline Kennedy, will not be placed on public display until 2103. Johnson's biographer Robert Caro wrote that Johnson wanted Jacqueline to be present at his swearing-in in order to demonstrate the legitimacy of his presidency to JFK loyalists and to the world at large.

Kennedy took an active role in planning her husband's state funeral, modeling it after Abraham Lincoln's service. She requested a closed casket, overruling the wishes of her brother-in-law, Robert. The funeral service was held at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington D.C. and the burial took place at nearby Arlington National Cemetery. Jacqueline led the procession on foot and lit the eternal flame — created at her request — at the gravesite. Lady Jeanne Campbell reported back to The London Evening Standard: "Jacqueline Kennedy has given the American people... one thing they have always lacked: Majesty."

A week after the assassination, the Warren Commission was established by President Johnson to investigate the assassination, with Chief Justice Earl Warren leading the investigation. Ten months later, the Commission issued its report with the conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone when he killed Kennedy. Privately, his widow cared little about the investigation, stating that even if they had the right suspect, it would not bring her husband back. Nevertheless, she gave a deposition to the Warren Commission. Following the assassination and the media coverage that had focused intensely on her during and after the burial, Jacqueline stepped back from official public view, apart from a brief appearance in Washington to honor the Secret Service agent, Clint Hill, who had climbed aboard the limousine in Dallas to try to shield her and the President.

Life following the assassination (1963–1975)

Mourning period and later public appearances

On November 29, 1963—a week after her husband's assassination—Kennedy was interviewed in Hyannis Port by Theodore H. White of Life magazine. In that session, she famously compared the Kennedy years in the White House to King Arthur's mythical Camelot, commenting that the President often played the title song of Lerner and Loewe's musical recording before retiring to bed. She also quoted Queen Guinevere from the musical, trying to express how the loss felt. The era of the Kennedy administration would subsequently often be referred to as the "Camelot Era," although historians have later argued that the comparison is not appropriate, with Robert Dallek stating that Kennedy's "effort to lionize [her husband] must have provided a therapeutic shield against immobilizing grief."

Kennedy and her children remained in the White House for two weeks following the assassination. Wanting to "do something nice for Jackie," President Johnson offered an ambassadorship to France to her, aware of her heritage and fondness for the country's culture, but she turned the offer down, as well as follow-up offers of ambassadorships to Mexico and Great Britain. At her request, Johnson renamed the Florida space center the John F. Kennedy Space Center a week after the assassination. Kennedy later publicly praised Johnson for his kindness to her.

Kennedy spent 1964 in mourning and made few public appearances during that time. In the winter following the assassination, she and the children stayed at Averell Harriman's home in Georgetown. On January 14, 1964, Kennedy made a televised appearance from the office of the Attorney General, thanking the public for the "hundreds of thousands of messages" she had received since the assassination and said she had been sustained by America's affection for her late husband. She purchased a house for herself and her children in Georgetown, but sold it later in 1964 and bought a 15th floor apartment at 1040 Fifth Avenue on Manhattan in the hopes of having more privacy.

In the following years, Kennedy attended selected memorial dedications to her late husband. She also oversaw the establishment of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, which is the repository for official papers of the Kennedy Administration. Designed by architect I.M. Pei, it is situated next to the University of Massachusetts campus in Boston.

Despite having commissioned William Manchester's authorized account of President Kennedy's death, The Death of a President, Jacqueline was subject to significant media attention in 1966–1967 when she and Robert Kennedy tried to block the publication. They sued publishers Harper & Row in December 1966; the suit was settled the following year when Manchester removed passages that detailed President Kennedy's private life. White viewed the ordeal as validation of the measures the Kennedy family, Jacqueline in particular, were prepared to take to preserve President Kennedy's public image.

During the Vietnam War in November 1967, Life magazine dubbed Kennedy "America's unofficial roving ambassador" when she and David Ormsby-Gore, former British ambassador to the United States during the Kennedy administration, traveled to Cambodia, where they visited the religious complex of Angkor Wat with Chief of State Norodom Sihanouk. According to historian Milton Osbourne, her visit was "the start of the repair to Cambodian-US relations, which had been at a very low ebb". She also attended the funeral services of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Atlanta, Georgia, in April 1968, despite her initial reluctancy due to the crowds and reminders of President Kennedy's death.

Relationship with Robert F. Kennedy

After the assassination, Kennedy relied heavily on her brother-in-law Robert F. Kennedy, observing him to be the "least like his father" of the Kennedy brothers. He had been a source of support early in her marriage after she had suffered a miscarriage; it was he, not her husband, who stayed with her in the hospital. In the aftermath of the assassination, Robert Kennedy became like a surrogate father for her children, until eventual demands by his own large family and his responsibilities as Attorney General required a reduction in attention. He credited her with convincing him to stay in politics, and she supported his 1964 run from New York for the United States Senate.

Following the January 1968 Tet offensive in Vietnam that resulted in a drop in President Johnson's poll numbers, Robert Kennedy's advisors urged him to enter the presidential race. When asked by Art Buchwald if he intended to run, Robert replied, "That depends on what Jackie wants me to do". She met with him around this time, encouraging him to run after previously advising him to not follow his brother, but to "be yourself". Privately, she worried about his safety, believing he was more disliked than her husband had been and that there was "so much hatred" in the United States. She confided in him about these feelings, but by her own account, he was "fatalistic" like her. Despite her concerns, Jacqueline campaigned for her brother-in-law and supported him, and at one point even showed outright optimism that through his victory, members of the Kennedy family would once again occupy the White House.

Just after midnight PDT on June 5, 1968, Robert Kennedy was shot and mortally wounded minutes after he and a crowd of his supporters had been celebrating his victory in the California Democratic presidential primary. Jacqueline Kennedy rushed to Los Angeles from Manhattan to join his wife Ethel, her brother-in-law Ted Kennedy, and the other Kennedy family members at his hospital bedside. Bobby Kennedy never regained consciousness and died 26 hours after the shooting.

Marriage to Aristotle Onassis

After Robert Kennedy's death, Kennedy reportedly suffered a relapse of the depression she had experienced in the days following her husband's assassination nearly five years prior. She came to fear for her life and those of her children, saying: "If they're killing Kennedys, then my children are targets ... I want to get out of this country".

On October 20, 1968, Kennedy married her long-time friend Aristotle Onassis, a wealthy Greek shipping magnate who was able to provide the privacy and security she sought for herself and her children. The wedding took place on Skorpios, Onassis's private Greek island in the Ionian Sea. Following her second marriage, she was now using the legal name Jacqueline Onassis and subsequently lost her right to Secret Service protection, which was an entitlement to a widow of a U.S. president. The marriage brought her considerable adverse publicity. The fact that Aristotle was divorced and his ex-wife was still living led to speculation that Jacqueline might be excommunicated by the Roman Catholic church, though that idea was explicitly dismissed by Boston's Archbishop, Cardinal Richard Cushing as "nonsense." She was condemned as a "public sinner," and became the target of paparazzi who followed her everywhere and nicknamed her "Jackie O".

During their marriage, the couple inhabited six different residences: her 15-room Fifth Avenue apartment in Manhattan, her horse farm in New Jersey, his Avenue Foch apartment in Paris, his private island Skorpios, his house in Athens, and his 325 ft (99 m) yacht Christina O. Kennedy ensured that her children continued a connection with the Kennedy family by having Ted Kennedy visit them often. She developed a close relationship with Ted, and he was involved in her public appearances from then on.

Aristotle Onassis' health began deteriorating rapidly following the death of his son Alexander in a plane crash in 1973, and he died of respiratory failure at age 69 in Paris on March 15, 1975. His financial legacy was severely limited under Greek law, which dictated how much a non-Greek surviving spouse could inherit. After two years of legal wrangling, Kennedy eventually accepted a settlement of $26 million from Christina Onassis—Aristotle's daughter and sole heir— and waived all other claims to the Onassis estate.

Later years (1975–1990s)

After the death of her husband, Onassis returned permanently to the United States, splitting her time between Manhattan, Martha's Vineyard, and the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis, Massachusetts. In 1975, she became a consulting editor at Viking Press, a position that she held for two years. After almost a decade of avoiding participation in political events, she attended the 1976 Democratic National Convention and stunned the assembled delegates when she appeared in the visitors' gallery. She resigned from Viking Press in 1977 following the false accusation by The New York Times that she held some responsibility for the company's publication of Jeffrey Archer novel Shall We Tell the President?, which was set in a fictional future presidency of Ted Kennedy and described an assassination plot against him. Two years later, she appeared alongside her mother-in-law Rose Kennedy at Faneuil Hall in Boston when Ted Kennedy announced that he was going to challenge incumbent President Jimmy Carter for the Democratic nomination for president. She participated in the subsequent presidential campaign, which was unsuccessful.

Following her resignation from Viking Press, Onassis was hired by Doubleday, where she worked as an associate editor under an old friend, John Turner Sargent, Sr. Among the books she edited for the company are Larry Gonick's The Cartoon History of the Universe, the English translation of the three volumes of Naghib Mahfuz's Cairo Trilogy (with Martha Levin), and autobiographies of ballerina Gelsey Kirkland, singer-songwriter Carly Simon, and fashion icon Diana Vreeland. She also encouraged Dorothy West, her neighbor on Martha's Vineyard and the last surviving member of the Harlem Renaissance, to complete the novel The Wedding (1995), a multi-generational story about race, class, wealth, and power in the U.S..

In addition to her work as an editor, Onassis participated in cultural and architectural preservation. In the 1970s, she led a historic preservation campaign to save from demolition and renovate Grand Central Terminal in New York. A plaque inside the terminal acknowledges her prominent role in its preservation. In the 1980s, she was a major figure in protests against a planned skyscraper at Columbus Circle that would have cast large shadows on Central Park; the project was cancelled, but a large twin-towered skyscraper, the Time Warner Center, would later fill in that spot in 2003.

Onassis remained the subject of considerable press attention, most notoriously involving the paparazzi photographer Ron Galella, who followed her around and photographed her as she went about her day-to-day activities; he took candid photos of her without her permission. She ultimately obtained a restraining order against him, and the situation brought attention to the problem of paparazzi photography. From 1980 until her death, Jacqueline maintained a close relationship with Maurice Tempelsman, who was her companion and personal financial adviser; he was a Belgian-born industrialist and diamond merchant who was estranged from his wife.

In the early 1990s, Onassis became a supporter of Bill Clinton and contributed money to his presidential campaign. Following the election, she met with First Lady Hillary Clinton, and advised her on raising a child in the White House. Clinton wrote in her memoir Living History, that Onassis was "a source of inspiration and advice for me", while Democratic consultant Ann Lewis viewed Onassis as having reached out to the Clintons "in a way she has not always acted toward leading Democrats in the past".

Illness, death and funeral

In November 1993, Onassis was thrown from her horse while participating in a fox hunt in Middleburg, Virginia and was taken to the hospital to be examined. A swollen lymph node was discovered in her groin, which was initially diagnosed by the doctor to be caused by an infection. In December, Onassis developed new symptoms, including a stomach ache and swollen lymph nodes on her neck, and was diagnosed with Ki1 non-Hodgkin lymphoma. She began chemotherapy in January 1994, and publicly announced the diagnosis, initially stating that the prognosis was good. While she continued to work at Doubleday, by March the cancer had spread to her spinal cord and brain, and by May to her liver. Onassis made her last trip home from New York Hospital–Cornell Medical Center on May 18, 1994. The following night at 10:15 p.m., she died in her sleep at age 64.

Following her death, John F. Kennedy Jr. stated to the press, "My mother died surrounded by her friends and her family and her books, and the people and the things that she loved. She did it in her very own way, and on her own terms, and we all feel lucky for that." On May 23, 1994, the funeral was held a few blocks away from her apartment at the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola, the Catholic parish where she was baptized in 1929 and confirmed as a teenager. She was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, alongside President Kennedy, their son Patrick, and their stillborn daughter Arabella. President Bill Clinton delivered a eulogy at her graveside service.

Onassis was survived by her children Caroline and John Jr., three grandchildren, sister Lee Radziwill, son-in-law Edwin Schlossberg, and half-brother James Lee Auchincloss. She left an estate that was valued at $43.7 million by its executors.

Legacy

Popularity

Jacqueline Kennedy remains one of the most popular First Ladies of the United States. She was featured 27 times on the annual Gallup list of the top 10 most admired people of the second half of the 20th century; this number is superseded by only Billy Graham and Queen Elizabeth II and is higher than that of any U.S. President. In 2011, she was ranked in fifth place in a list of the five most influential First Ladies of the twentieth century for her "profound effect on American society." In 2014, she ranked third place in a Siena College Institute survey, behind Eleanor Roosevelt and Abigail Adams. In 2015, she was included in a list of the top ten influential U.S. First Ladies due to the admiration for her based around "her fashion sense and later after her husband's assassination, for her poise and dignity."

Kennedy is seen as being customary in her role as First Lady, though Magill argues her life was validation that "fame and celebrity" changed the way First Ladies are evaluated historically. Hamish Bowles, curator of the “Jacqueline Kennedy: The White House Years” exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, attributed her popularity to a sense of unknown that was felt in her withdrawal from the public which he dubbed "immensely appealing." Writing after her death, Kelly Barber referred to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis as "the most intriguing woman in the world", furthering that her stature was also due to her affiliation with valuable causes. Historian Carl Sferrazza Anthony summarized that the former First Lady "became an aspirational figure of that era, one whose privilege might not be easily reached by a majority of Americans but which others could strive to emulate.” Since the late 2000s, Kennedy's traditional persona has been invoked by commentators when referring to fashionable political spouses.

A wide variety of commentators have credited Kennedy with restoring the White House; the list includes Hugh Sidey, Leticia Baldridge, Laura Bush, Kathleen P. Galop, and Carl Anthony.

Tina Turner and Jackie Joyner-Kersee have cited Kennedy as influencing them.

Style icon

During her husband's presidency, Jacqueline Kennedy became a global fashion icon. She retained French-born American fashion designer and Kennedy family friend Oleg Cassini in the fall of 1960 to create an original wardrobe for her as First Lady. From 1961 to late 1963, Cassini dressed her in many of her most iconic ensembles, including her Inauguration Day fawn coat and Inaugural gala gown, as well as many outfits for her visits to Europe, India, and Pakistan. In 1961, Kennedy spent $45,446 more on fashion than the $100,000 annual salary her husband earned as president. Although Cassini was her primary designer, she also wore ensembles by French fashion legends such as Chanel, Givenchy, and Dior.

As a First Lady, Kennedy preferred to wear clean-cut suits with a skirt hem down to middle of the knee, three-quarter sleeves on notch-collar jackets, sleeveless A-line dresses, above-the-elbow gloves, low-heel pumps, and pillbox hats. Dubbed the "Jackie" look, these clothing items rapidly became fashion trends in the Western world. More than any other First Lady, her style was copied by commercial manufacturers and a large segment of young women. Her influential bouffant hairstyle, described as a "grown-up exaggeration of little girls' hair," was created by Kenneth Battelle, who worked for her from 1954 until 1986.

In the years after the White House, Kennedy's style underwent a change, with her new looks consisting of wide-leg pantsuits, large lapel jackets, gypsy skirts, silk Hermès head scarves, and large, round, dark sunglasses. She often chose to wear brighter colors and patterns and even began wearing jeans in public. Beltless, white jeans with a black turtleneck, never tucked in, but pulled down over the hips, was another fashion trend that she set.

Throughout her lifetime, Kennedy acquired a large collection of jewelry. Her triple-strand pearl necklace, designed by American jeweler Kenneth Jay Lane, became her signature piece of jewelry during her time as First Lady in the White House. Often referred to as the "berry brooch," the two-fruit cluster brooch of strawberries made of rubies with stems and leaves of diamonds, designed by French jeweler Jean Schlumberger for Tiffany & Co., was personally selected and given to her by her husband several days prior to his inauguration in January 1961. She wore Schlumberger's gold and enamel bracelets so frequently in the early and mid-1960s that the press called them "Jackie bracelets"; she also favored his white enamel and gold "banana" earrings. Kennedy wore jewelry designed by Van Cleef & Arpels throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s; her sentimental favorite was the Van Cleef & Arpels wedding ring given to her by President Kennedy.

Kennedy was named to the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1965. Many of her signature clothes are preserved at the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum; pieces from the collection were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2001. Titled "Jacqueline Kennedy: The White House Years," the exhibition focused on her time as a First Lady.

In 2012, Time magazine included Kennedy on its All-TIME 100 Fashion Icons list.

In 2016, Forbes included her on the list 10 Fashion Icons and the Trends They Made Famous.

Honors and memorials

- A high school named Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis High School for International Careers, was dedicated by New York City in 1995, the first high school named in her honor. It is located at 120 West 46th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, and was formerly the High School for the Performing Arts.

- The main reservoir in Central Park, located in New York City, was renamed in her honor as the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir.

- The Municipal Art Society of New York presents the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Medal to an individual whose work and deeds have made an outstanding contribution to the city of New York. The medal was named in honor of the former MAS board member in 1994, for her tireless efforts to preserve and protect New York City's great architecture. She made her last public appearance at the Municipal Art Society two months before her death.

- At George Washington University, a residence hall located on the southeast corner of I and 23rd streets NW in Washington, D.C., was renamed Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis Hall in honor of the alumna.

- The White House's East Garden was renamed the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden in her honor.

- In 2007, her name and her first husband's were included on the list of people aboard the Japanese Kaguya mission to the moon launched on September 14, as part of The Planetary Society's "Wish Upon The Moon" campaign. In addition, they are included on the list aboard NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission.

- A school and an award at the American Ballet Theatre have been named after her in honor of her childhood study of ballet.

- The companion book for a series of interviews between mythologist Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, was created under her direction prior to her death. The book's editor, Betty Sue Flowers, writes in the Editor's Note to The Power of Myth: "I am grateful... to Jacqueline Lee Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, the Doubleday editor, whose interest in the books of Joseph Campbell was the prime mover in the publication of this book." A year after her death in 1994, Moyers dedicated the companion book for his PBS series, The Language of Life as follows: "To Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. As you sail on to Ithaka." Ithaka was a reference to the C.P. Cavafy poem that Maurice Tempelsman read at her funeral.

- A white gazebo is dedicated to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis on North Madison Street in Middleburg, Virginia. The First Lady and President Kennedy frequented the small town of Middleburg and intended to retire in the nearby town of Atoka. She also hunted with the Middleburg Hunt numerous times.